To Southeast Asia with love, and reading Goliath’s Curse

It’s now two weeks since we got back from a two-week trip to Southeast Asia. The travelling was tough, but worth it. There was lush tropical beauty, ancient culture, and vibrant trade. Once I got over the severe jet lag, I felt changed in a good way.

We flew from Raleigh to Seattle, and then to Seoul, and then to Hong Kong, where we boarded the Viking ship Orion. After a day of sight-seeing in Hong Kong, we set sail for Vietnam, Cambodia, and Thailand.

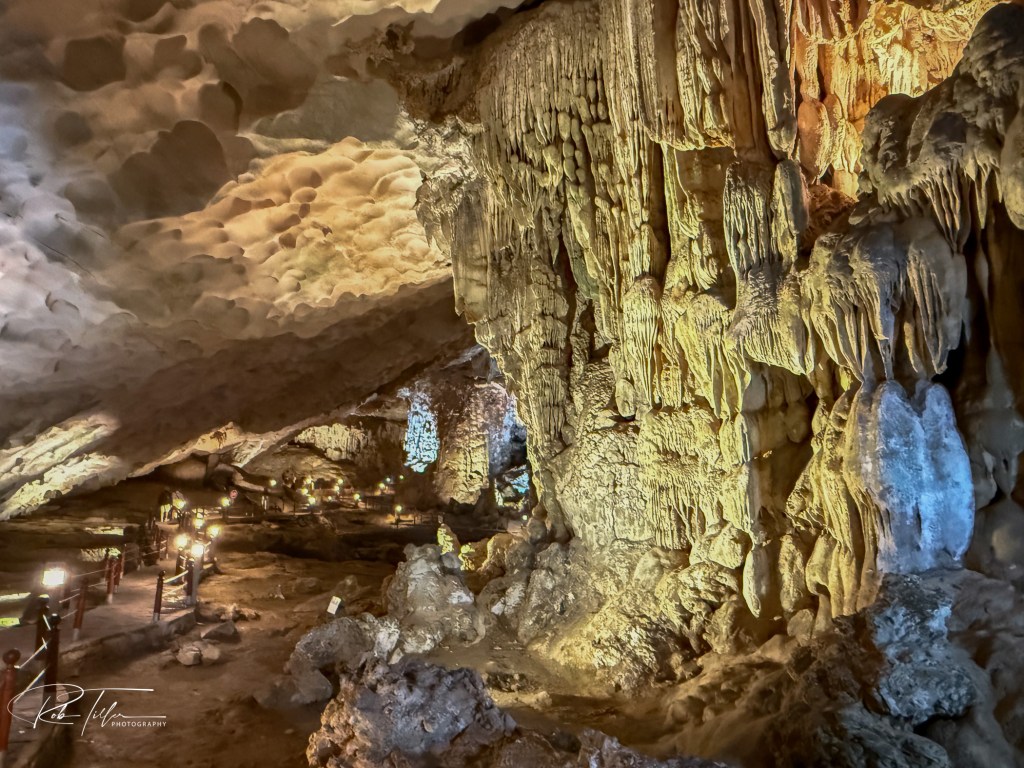

Trip highlights included Ha Long Bay, Vietnam, where there are hundreds of dramatic limestone islands; Hoa Lu, an ancient capital where we visited a temple and took a lovely row boat trip; Hoi An, where we saw the grimier aspects of the country, a traditional medicine shop, silk manufacturing, and temples; Ho Chi Minh City (a/k/a Saigon) with modern high rises, teeming markets, and waves of hundreds of motorbikes; Siem Reap, Cambodia and the enormous temples of Angkor Wat, Thom Wat, and Ta Prohm; and the huge, modern city of Bangkok. The Orion was like a first class hotel, beautifully appointed and serviced, and Viking provided good tour guides.

Based on our short encounters, we found the Vietnamese people to be generally friendly and helpful, but business-like and hardworking. Cambodians seemed more relaxed and laid back, though the street vendors were surprisingly aggressive. For Bangkok we were mostly touring by bus, so we didn’t have many close personal encounters.

I was interested in learning about the local religions. I’ve long been interested in Buddhism, but I quickly figured out that Buddha’s original teachings, as they’d come to me, were barely recognizable in the religion as practiced in Southeast Asia today. The local versions seemed to combine worship of Buddhist icons with elements of other traditions, including Taoism, Confucianism, Hinduism, and animism. The temples, with their elaborate ornamentation, seemed undogmatic and undemanding.

This was less true of Angkor Wat, which is the largest religious complex on Earth. Built in the 12th century, it’s now mostly a ruin, but enough is left to show that its builders were highly serious about their religion as well as their armies. A later generation of Hindus destroyed many of the icons, and most recently many statues of Buddha were decapitated by looters and the heads sold abroad.

During the trip I read Saigan, a historical novel by Anthony Grey. (Thanks to my friend J, an old Vietnam hand, for recommending it.) It resembled a James Michener novel in good ways, with a broad overview of Vietnam’s history in the 20th century woven together with some interesting characters. Grey taught me some new things about the brutality of the French colonial regime, and brought key battles of the American war to life. As with Michener, the prose was not especially beautiful, but I still found the book quite worthwhile.

I learned a bit about the current Vietnamese system of government, which is managed by the Communist Party of Vietnam. Opposing political parties and criticism of the CPV is not permitted. But much economic activity is indistinguishable from the mostly free markets of the West. At street level, it doesn’t look particularly unfree. In fact, in places it looks highly energetic and dynamic.

During the trip, I also delved into an important and fascinating new book, Goliath’s Curse: The History and Future of Societal Collapse, by Luke Kemp. Kemp, who is affiliated with Cambridge, examines the archaeological evidence of earlier large states and empires (“Goliaths”) looking for the factors that led to their collapse. Like Graeber and Wengrow in The Dawn of Everything, Kemp challenges the conventional narrative of orderly human progress beginning with agriculture, and the assumption that increasing size and complexity of government is natural and unavoidable.

Kemp finds that a key predictor of societal collapse across the centuries is extreme inequality. Increasing inequality generally arises from domineering elites extracting resources (such as minerals, crops, and taxes). Elite domination and corruption results in resentment and rebellion. Combined with other factors, such as exhaustion of natural resources, war, disease, or climate change, extreme inequality can result in societal collapse.

Goliath’s Curse is a timely book. If Kemp is right, the extreme inequality in the U.S. and many other countries is a flashing red danger sign. Dissatisfaction with this inequality has already begun to undermine our traditional democratic institutions by ushering in the age of Trump. Kemp suggests that there is a possible path out of our current crisis: reducing inequality and increasing democracy.

On the long (31 hour) trip home, among other things, I watched for the second time Don’t Look Up (2021), the dark satire about two astronomers (Leonardo DiCaprio and Jennifer Lawrence) trying to warn of a comet on a collision course with the planet. Merryl Streep is a hoot as a Donald-Trumpish president who tries to profit from and divert attention from the coming catastrophe. As Trump continues to lead the insane battle against addressing climate change, the movie remains very much of the moment.