Wild horses, and a proposal for new thinking about animals

Last week we had a family vacation at Corolla, a community on the Outer Banks of North Carolina. Early every morning I went for a drive on the beach to look for the wild horses that live there. Most days I didn’t see any, but one day I did. Here are a few images of them.

I wanted to share a few more of my photos of bears and other creatures from my recent Alaska trip, so I made a short (4 minute) slide show of some of my favorites and put it on YouTube. You can find it here.

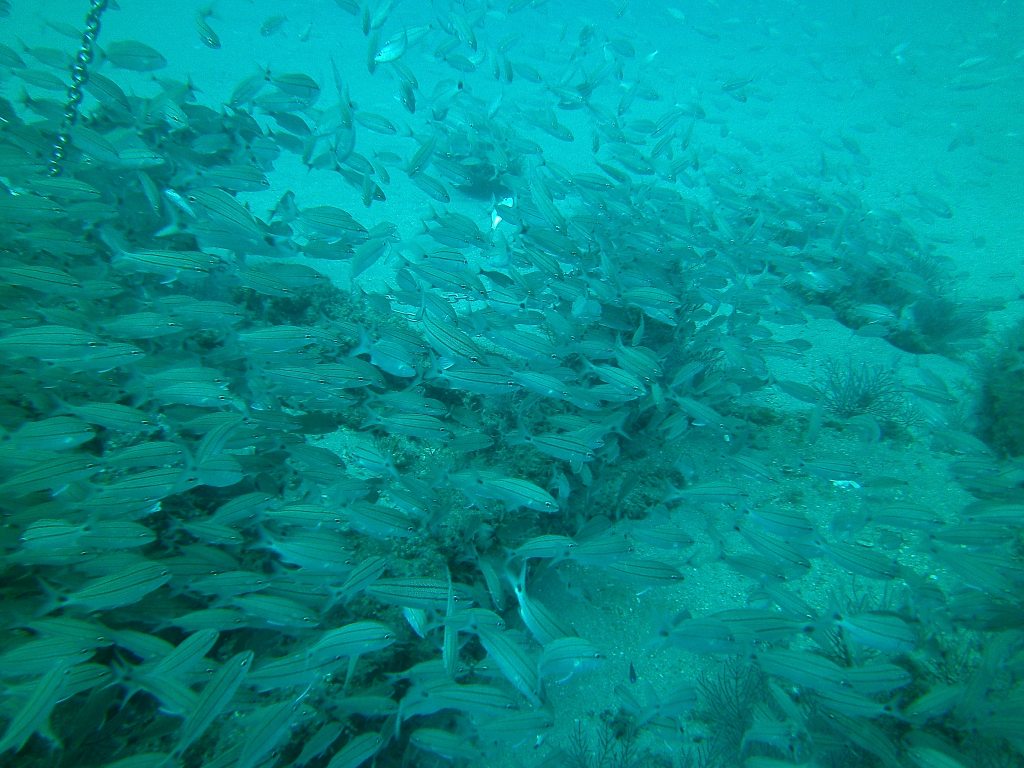

One of the things I value about wildlife photography is getting to know the animals better. Of course, it’s very rewarding to spend time in the field with other creatures. But also, reviewing the still images, I always get some new insights into the lives they live, and I hope others do, too.

Non-human animals have hard lives, and in general humans make their existence harder. Part of the problem, I think, is the widespread failure to see members of other species as more than mere objects to be exploited. I hope my photography helps to challenge that view, and suggests how we might see each creature as worthy of respect and compassion.

I’m afraid that in general, people don’t have much interest in non-human animals, unless they can be eaten or exploited for profit or amusement. This has been true for a long time. This way of thinking is problematic for people as well as other animals, and I’ve been thinking a lot about why it is so pervasive, and how it might change.

It seems natural to enjoy being with other creatures, and indeed, young children bond easily with them. But from an early age, we are taught that they are essentially different from us, and inferior. The lesson is pounded in, over and over: humans are not animals, and animals are inferior to humans.

The idea that humans are not animals is not only questionable – it’s wrong. It has nothing in science or reason to back it up. Darwin debunked it more than a century and a half ago, and his basic theory has been repeatedly tested and confirmed. From an evolutionary perspective, all living animal species, including homo sapiens, are closely related to each other.

Moreover, as scientific knowledge has expanded, it’s obvious that non-humans have many similar sensory capacities to humans, and some have vision, hearing, smell, touch, or other unusual senses that are vastly more acute.

There have been various qualities we once supposed made humans unique, including reasoning ability, memory, tool use, planning, and problem solving. But one by one, with more studies of more species, those ideas have turned out to be the product of our ignorance, as first one and then many creatures demonstrate such capacities in various degrees.

So why do homo sapiens persist in believing that we’re separate and apart, and superior? It’s plainly a flattering thought – we’re number one! And if we’re confident that non-humans are vastly inferior, we can justify eating them and otherwise treating them with indifference and terrible cruelty. It’s convenient.

But I’m coming to think that the notion that privileges humans over non-human animals is part of a pervasive, and deeply flawed, thought system. Our various ideas of inherent superiority and inherent inferiority are interconnected and mutually reinforcing. They form a powerful network that limits our appreciation of each other and the natural world.

Beliefs that one race is superior to another, that men are superior to women, or that straight is superior to gay, are all without any scientific basis. The same is true for holding Ivy League grads to be fundamentally superior to non-Ivies, white collars over blue collars, or homeowners over homeless. The list of our arbitrary and baseless hierarchical gradations goes on and on.

Nevertheless, they are so deeply ingrained in our consciousness as to seem part of nature. Like the belief in the superiority of humans over other animals, they’re part of our habitual way of thinking – that is, our culture.

Hierarchical thinking – deeming one group inferior to another – is more advantageous to some than others, but even those lower in the caste system accept at least some of it as natural and good. An example is poor working whites, who historically have found solace in the baseless notion that they are at least superior to Blacks. And racial and religious minorities have their own within-group grading systems based on skin color, wealth, education, and other factors.

As for non-human animals, almost all humans put them at the bottom of their hierarchies. They are still the standard metaphor for those who are most frightening and least deserving, as in “those awful [insert group name here] are animals”! We rank some animals over others, such as our dogs over pigs, but even the favored species members are usually deemed expendable objects, rather than beings with inherent dignity.

The fundamental problem with such hierarchical thinking is that it is divisive. Human hierarchies divide us from each other, and make it difficult to appreciate and bond with others. Even those high up in hierarchies are emotionally limited and morally depleted by the system. The hierarchies foster defensiveness, paranoia, and hate. At the same time, they lessen the opportunities for loving connection.

Our delusions of natural hierarchies do enormous damage, but they haven’t destroyed all our intuitions of fairness or our ability to perceive individuals. Though deeply embedded, those notions are subject to change.

In my lifetime, we’ve managed to revise for the better some of our worst prejudices on race, patriarchy, and minority sexuality. There’s even been progress in seeing animals as more than mere objects. For example, we’ve reduced the slaughter of whales, elephants, and certain other creatures, and acknowledged the injustice of our driving various species to extinction.

But there’s a lot of work still to be done, both for disfavored humans and non-humans. I don’t have a comprehensive solution, but I do have an idea for where to start: respect and compassion. These are attitudes we all know something about. Most all of us have respect and compassion for at least a few others, and to get started we can build on that.

I propose the following experiment. For each being we encounter, let us try saying to ourselves, “Although we are different, I respect you as an individual and wish you well.” This reorientated attitude would change us, in a small way, and multiplied enough times, would make a vast change.

I’ve been doing this experiment, and I think it has changed me and my surroundings a bit for the better. Recently a family of deer with two spotted fawns has been quietly visiting our yard to graze. While admiring their beauty and grace, I’ve been consciously seeing them as individuals with their own concerns. It’s hard to tell what they think, but they’ve certainly noticed me, and don’t run away. They definitely like our grass.