More on our South African safari and new discoveries on birds and plants

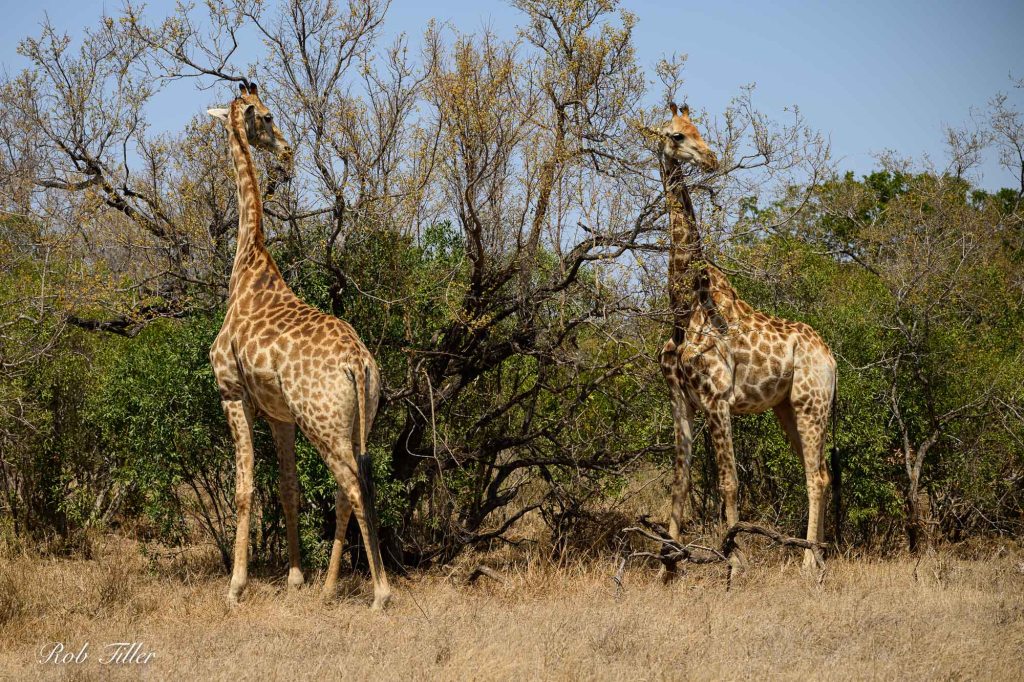

I finally finished going through the thousands of pictures I took during our South Africa safari, and found a few more I wanted to share.

During the safari, we saw animals doing many of the things we know they have to do, like eating, drinking, bathing, teaching their young, and mating. We didn’t see any actual kills, but we did see several big cats feeding on recent kills. I debated whether to share photographs of those, since it’s unavoidably sad, and perhaps upsetting, to deal with the death of a beautiful creature like an impala. But I also see an element of beauty in the predator and his or her success.

The lions, leopards, and cheetahs must kill to survive and to feed their young. It’s just the way they’re made. It turns out that it’s quite difficult for them to hunt successfully, and they often fail. Grazing animals are highly sensitive to predator risks, and most of them are, when healthy, either faster or stronger than their predators. On this trip, we watched a hidden lion lie in ambush for lengthy periods hoping, unsuccessfully, for an unwary zebra or impala.

The grazing animals that the big cats catch are generally the old, young, or ill. In fact, their hunting is important for the health of the grazing herds. It keeps diseases in check and prevents overpopulation and overgrazing that would lead to more death. Nature generally manages to keep things remarkably well balanced among predators, prey, and plants, when there isn’t human interference.

There’s a vast amount that we do not know about nature, which is exciting, in a way: there’s so much more to learn. This week the New Yorker had a lively and interesting piece by Rivka Galchen about what scientists are learning about bird song.

I’ve been interested in bird song for many years, but mainly as a way to identify birds that won’t allow themselves to be seen. From watching flocks of big birds like tundra swans and Canada geese, I’d come to suspect that their vocalizations allowed them to coordinate their travels together. Now researchers are confirming the suspicion that their sounds have a lot of communicative content.

Scientists have long recognized that birds make specific alarm calls, and are learning that some of those calls differentiate the threats of, say, a hawk or a snake. It turns out that bird parents make sounds while incubating their eggs that the developing baby bird learns. We’re learning that bird communication is more complex than we thought, which indicates that their intelligence is more complex than we thought.

With fall arriving, it’s gotten a bit chilly for me to have my morning tea on our deck, but when it’s mild I like to sit out there as the sun is rising and listen to the birds. I’ve been using the Merlin app to identify calls and songs I don’t already know. The app has gotten a lot better over the last couple of years, and is almost always accurate, at least as to the birds I’m familiar with.

Speaking of the natural world, I’m in the midst of a remarkable book about plants: The Light Eaters: How the Unseen World of Plant Intelligence Offers a New Understanding of Life on Earth, by Zoe Schlanger. Schlanger has reviewed the scientific literature and interviewed leading botany experts researching how plants sense the world and deal with their environments. Her style is friendly and approachable, and her content is at times mind blowing.

It turns out that plants are much more proactive than we used to think. There are species that modify their chemistry in response to predators to make themselves less appetizing. There are ones that send out chemical signals to warn others of their kind of particular predators. Some even send out chemical signals to summon insects that will prey upon the plants’ enemies.

There is considerable evidence that plants respond to touch. Some researchers have found that they respond to certain sounds, which we might call hearing. They modify their behavior to avoid threats and to improve their nutrition. The puzzle is that they lack a clear hearing organ, like an ear, or a centralized interpretive organ, like a brain. How they do it is yet to be discovered.

But it’s hard to avoid the thought that plants are in some sense conscious. Schlanger recognizes that the idea of plant intelligence is still controversial in the botanical science world, and gives credit to scientists for being cautious and careful. In this time of great anxiety about the human world of politics and war, her new book is a welcome reminder that, quite apart from humans, the world has been and continues to be full of wonders.